Hi all. This is the second post in my new weekly series in which I discuss one of my original compositions off the latest Tyler Mire Big Band CD, #Officefortheday. In these discussions I hope to go over my writing process, concepts I employ, and other misc. facts about the tunes. For those interested in checking out this CD, you can pick it up on CDBaby, iTunes, or Google Play.

For the first week we covered the Basie-like swinger “The Lonely Crouton’s Big Day in NYC”. Today we will cover the funky rhythm changes tune “#Officefortheday”.

Here’s the score, now let’s follow along with the track:

I recommend listening through the piece while following the score once or twice before proceeding further.

Similar to “The Lonely Crouton’s Big Day in NYC”, “#Officefortheday” was started by limiting options. Here were some of the decisions I made before I started writing:

-Groove would alternate between Hip Hop and Swing.

-The form would come from Rhythm Changes.

-Written out bass line.

I recently gave a talk about this chart and my writing process at a George Mason jazz arranging class. I explained how these three decisions really helped provide solutions before I started writing. For instance, knowing that the tune will be over Rhythm Changes (AABA) and understanding that I want a groove that alternates between Hip Hop/Swing, I deduced that the Bridge (B Section) of Rhythm Changes makes more sense to be the Swing sections. Likewise, wanting a written out bass line, it made more sense to use it with the Hip Hop sections, as bass lines in that style aren’t as specific as Swing (walking bass).

I also had another small issue with my own band to solve. You see, the majority of my band’s repertoire was written for specific soloists and lasted a specific number of bars. I knew that on certain gigs I would want some tunes that had more flexibility. Having an open solo section over a classic jazz form (Rhythm Changes) would allow me to give anyone a chance to solo. And the live recordings of #Officefortheday bear this out. I would regularly have 2-3 different soloists a night depending on the set. Also, having an open section over a standard jazz form allows the music to breathe. I found these moments during our live performances to be the most inspired. That isn’t to say every tune needs to have an open section, I actually strongly disagree with that concept, but having a tune or two with some flexibility can balance out the more specifically composed pieces.

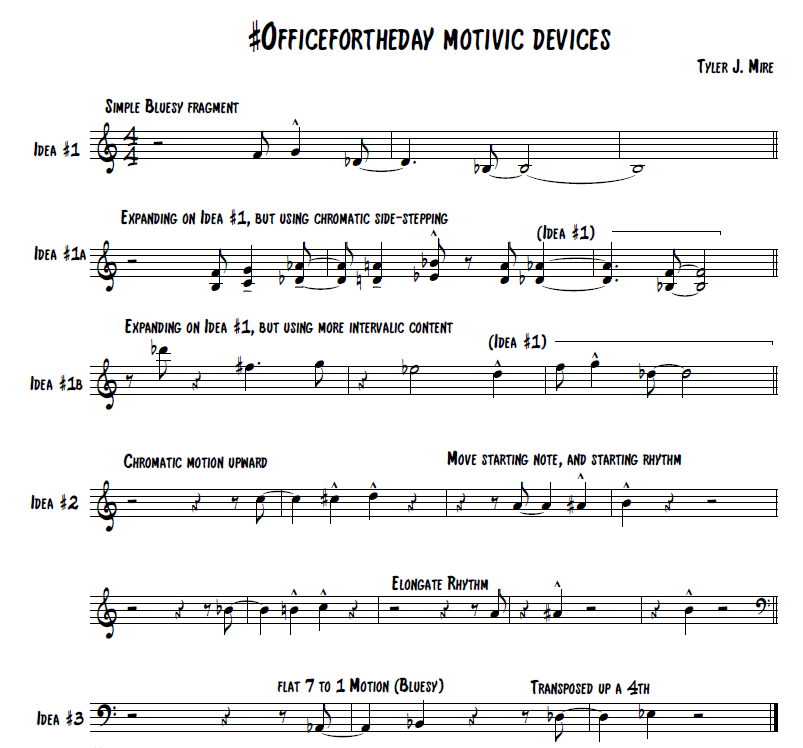

I do not intend to go into too much depth over these choices in this blog post. Rather, I want to spend this post focusing on my use of melodic development in #Officefortheday. Something I didn’t really touch on with the last post was how one of my main goals when composing is that no matter how complex the music gets, the melody should be the central element that helps guide the listener. In the George Mason class, I joked to the students that #Officefortheday was basically just a chart of four ideas. Turns out, it was closer to the truth than I thought. With that being said, let’s take a look at some of the melodic material I used in #Officefortheday:

We’ll be referring to these ideas often, so if you need to, save the image and have it handy. I’ll take us from the beginning of the tune up to the solo section and show you how I used these ideas.

Making the most out of a little:

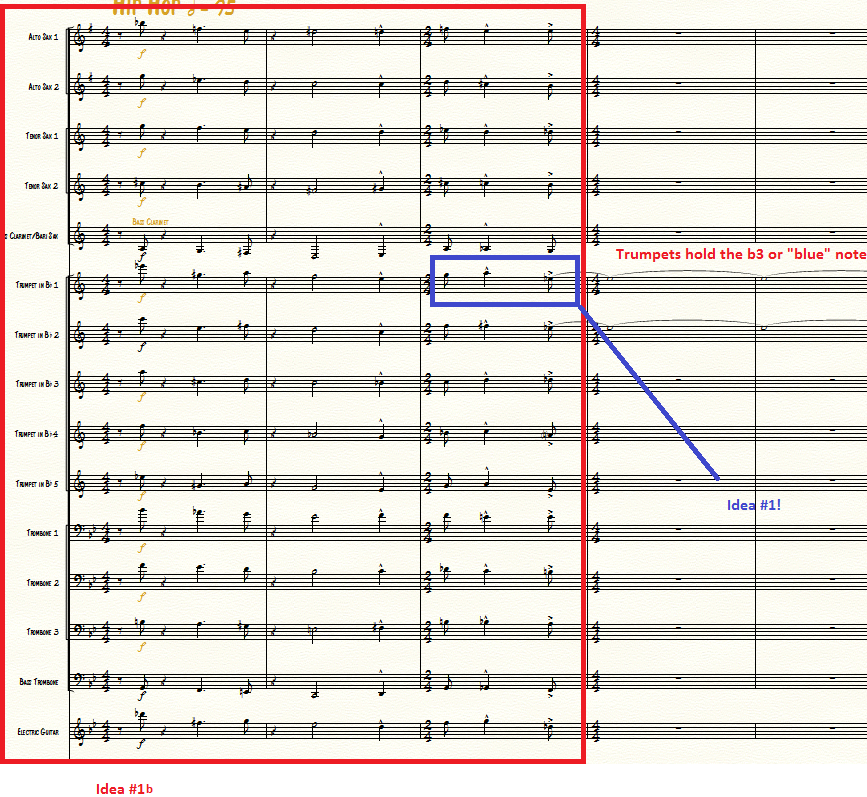

The beginning of the chart begins with a “cold open”. Bam! Right out the gate. It gets the listener excited and sets up what will come later:

The top two trumpets hold over a concert Db (b3 of the key) setting a vibe before the next material is introduced. Similar to “The Lonely Crouton’s Big Day in NYC”, this tune then launches into a mini overture. I use it as an opportunity to introduce the listener to most of the melodic material they will be hearing throughout the piece. The first main idea to happen is the bass line – or Idea #3:

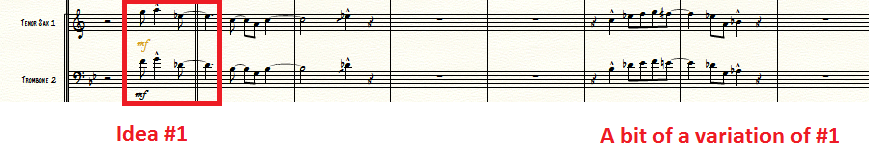

This bass line will continually be developed throughout the chart, ending with its final form at letter Q. One quick note is the instrumentation choice of Acoustic Bass, left hand Piano and Bass Clarinet. To me, this gives it a real fat and funky sound. The sound of the bass strings and the reediness of the bass clarinet, really compliment each other in my opinion. Originally, the first draft of the chart had Electric Bass, but I realized that it created problems when going to Swing and it was too heavy sounding on the Hip Hop sections. Later on in the chart when I want it a little beefier, I add Bass Trombone and have Baritone Saxophone substitute the Bass Clarinet. After the bass groove is established to the listener, I re-introduce Idea #1 with Tenor 1 and Trumpet 5 :

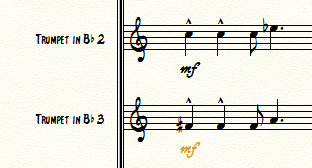

A few bars later, two trumpets answer with a similar melodic fragment:

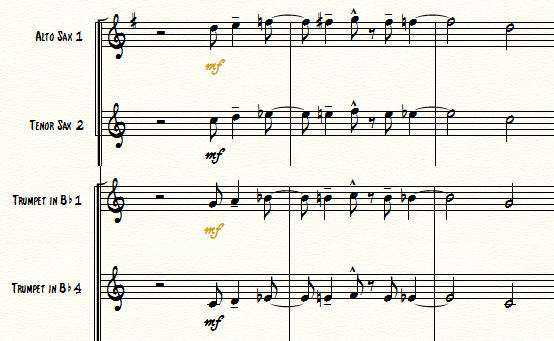

Note the use of b3 and 1, but in the reverse order. I harmonize in a tritone to get a comical, taunting like effect. I use this fragment again in the main melody. Moving on we see the first example of Idea #1a:

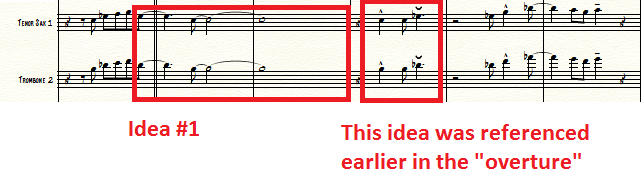

This small group of horns allows them to really play light and stylize together. The rest of the “overture” basically develops these ideas by adding more instruments. It cultivates with a big fat Bb13(#11) voicing in bar 47! This is very surprising for the listener. It is also challenging for the band, especially the trumpets! (Don’t write things like this unless you have some serious pros in the section)! We then get to the melody (first A section of an AABA tune) which is played by Tenor 1, Trombone 2, and Guitar (with wah-wah). I employ several of the previous ideas but in a more linear way:

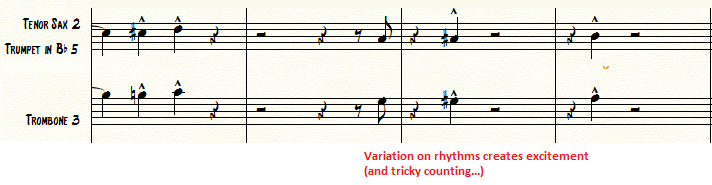

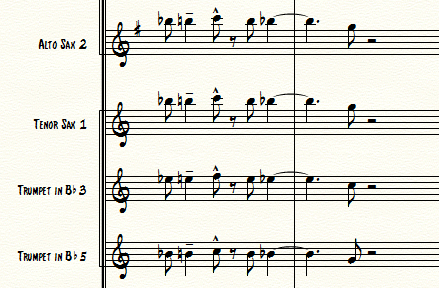

The bridge is the first time we hear Idea #2 and a Swing feel. As stated earlier, I knew I wanted to have a groove contrast. With that I knew I needed to present contrasting melodic material in the bridge. Due to the previous ideas all being based on minor pentatonic scales with a large emphasis on minor 3rd and major 2nd intervals, I determined that a more half step approach might provide the most interesting contrast. Due to this bridge melody not being as melodic, I utilized repetition and rhythm to create interest:

The variation on rhythms creates excitement and surprise to the listener. By the fourth iteration of the fragment, the listener has already heard it three times, giving you some leeway to change it. As you may have noticed, I used space in the phrases to invite the rhythm section in. Throughout the piece, the piano part is very specific, so this allows great players (like Matt Endahl) to have a chance to comment in the moment. Also of note, is that up to this point I have kept the orchestration light. Any particular idea is carried by three or four instruments at most. I’d advise writers to resist the urge to always write entire sections together. This will allow the orchestration to sound bigger when you finally do use full-tuttis. Moving on we return to our last A section. At this point I’m building the dynamics by adding more instruments – Trumpet 4 and Alto 2 to the melody – and Bass Trombone to the bass line. I also punctuate the spaces with fat punches. This is all leading to our eventual send off to our solo section. After Trumpet 1 states Idea #1 again, we get another appearance by Idea #1a, with a slightly truncated rhythm:

Then we finally have our first full band tutti! The chart really feels that it’s arrived somewhere and it’s time to start playing some jazz! Enjoy the great solos by Jim Williamson (Trumpet), Lindsey Miller (Guitar), and Doug Moffet (Tenor). The rest of the chart is a continuation of these principles. I encourage you to explore the score and see other areas where I developed the basic melodic fragments. Using these strategies I was able to get a lot of mileage out of a relatively small amount of material.

I truly believe that I have gotten better at composing by doing. I’ve studied scores, listened to hundreds of big band recordings and played thousands of big band charts. All this helps. But I’ve learned a lot more from writing charts. Most of the charts I’ve written are not good. In fact if I were to spend time looking at my older charts I’d find a plethora of mistakes and regrets. (Side note: Gordon Goodwin did a nice blog post about this very subject). But with each new chart I write I strive to improve and challenge myself in new ways. For young writers, I highly recommend finding your own creative outlets to compose for. With all that said, I think it’s best to wrap up this post by drawing some larger points.

Lessons Learned from #Officefortheday:

Repetition is fine, but repetition with variation is better.

-Don’t be afraid to reuse material to “hook” the listener.

-Repetition with variation gives the piece structure while providing the listener a frame of reference. Variation provides surprises and interest by subverting expectations you have established.

-When revisiting material for climaxes, use your tools of timbre, range, and orchestration to reintroduce material in a more exciting way. (See: Letter Q)

Keep your voicings simple

-Don’t reinvent the wheel, your basic voicings will go far. Trombones supply chord tones (3rds and 7ths) and Trumpets play triadic shapes within an octave. This will work majority of the time.

-Use your saxes as a way to “EQ” the brass when in tutti. Think of them as the glue that connects and gives cohesion to the brass section.

-Find interesting color through contrary motion (between bass and lead line – see 3 before Q) and using add-chords over static lead lines (see: 4 before H).

Resist the temptation to “over write”.

-Getting dynamic contrast in big band is a challenge, so using smaller groups of horns can be effective.

-When using full band together, the listener will feel the weight and drama of the group playing at once! Think of your ensemble as an orchestra and resist the urge to have everyone playing together all the time!

-Sections used in full-tutti are very effective (see Letter P)! Use it to your advantage.

Use your rhythm section!

-The rhythm section can provide interesting textures if not overwritten with horns (see above). Giving an open solo with no backgrounds allows the soloist and rhythm section to interact, effectively putting the chart in the rhythm section’s court for that period of time. With great players, great music can be made if you get out the way!

Don’t be afraid to piggy back.

-Cliches have power. Tropes are tools. #Officefortheday borrows from Rhythm Changes, one of the most played chord changes of all time. Simple bluesy ideas are everywhere in this chart! Writing with common language is a way to give your players a performance template without having to explain it. This is our shared language as jazz musicians.

Tell a story.

-Have an end goal in mind for each piece you write. Think of your motivic devices as characters and rhythm/harmony/texture as your setting and story.

-Craft meets imagination. Try to continually sharpen your composing tools so you can more clearly express your musical ideas.

Thank you again for reading this post! As always, if you enjoyed this please contact me on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter. If you’d like to pick up the new album you can get it on CDBaby, iTunes, or Google Play.

All the best,

Tyler