Hi all. This is the first of what I hope to be a weekly series in which I discuss one of my original compositions off the latest Tyler Mire Big Band CD, #Officefortheday. In these discussions I hope to go over my writing process, concepts I employ, and other misc. facts about the tunes. For those interested in checking out this CD, you can pick it up on CDBaby, iTunes, or Google Play.

Our first tune we will cover is the oddly titled “The Lonely Crouton’s Big Day in NYC.” The title is credited to Evan Cobb, the first tenor player of the TMBB and a close friend of mine. Back in the fall of 2015, we were both on the road with Anderson East for a few weeks and one of our stops was in New York City. I can’t remember where we were exactly, but there was this curious crouton on the floor and Evan blurted out the title. True story. Ok, so it may not be EXACTLY like that, but that’s how I remember it. With that out the way, let’s proceed.

Here’s the score, now let’s follow along:

Often younger students ask me how I start a new writing project. They are overwhelmed with their options. I am a firm believer in the adage, “Limitations breed creativity”. So in that respect, I like to limit my options before I start. The following were what I aimed to do with this composition:

-Medium Basie Swing

-Explore 2/3 key centers.

-Sus chords over a pedal point.

-Sax soli.

-Feature Jim Williamson (Flugel) and Roger Bissell (Trombone).

-Traditional shout chorus to feature ensemble in tutti.

Whew! That seems like a lot doesn’t it? Let’s break each point down one a time.

1. Medium Basie swing

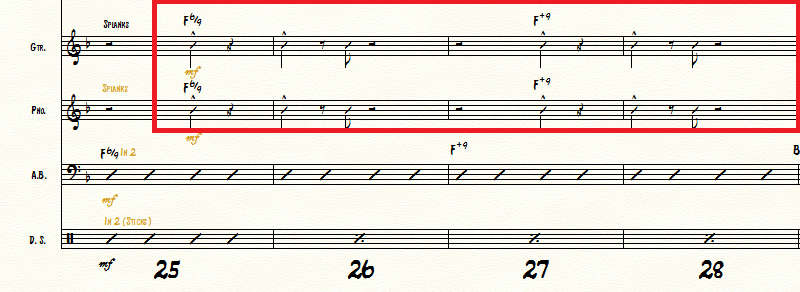

The “Basie swing” style comes with a lot of connotations. For this I wanted to focus on a more relaxed medium tempo. In order to capture some Basie-like elements, I introduced “splanks” to the guitar and piano in the first A behind the horns:

Another method I used to capture the sound of medium Basie swing is by indicating Freddie Green style comping in the guitar part. For those who are unaware, Freddie Green was Count Basie’s guitarist for over 40 years who was known for his steady quarter note comping style, which is highly emulated in big band guitar playing. For any guitarist, this knowledge of the style is expected and Lindsey Miller nails it. After hovering over a pedal point and then playing in two the quarter notes in the guitar and bass really allow the groove to have momentum (starting at m.39).

2. Explore 2/3 key centers

While on tour with Anderson East, Evan and I went to the Jazz Standard and heard a wonderful concert by Ryan Truesdale’s Gil Evans Project. While listening, Evan pointed out to me how Gil’s tunes weren’t the typical AABA type of tunes, but rather more through-composed, with solo sections starting and ending on odd parts of the form and modulations occurring in different sections. I was inspired by this and was determined to try and utilize this concept in this tune. The first A section of the tune is in the key of F, but when the saxes comes in with the melody (m. 41) we modulate to the key of Ab (which I’ll call the A prime section). Likewise, the saxophone soli starts in the key of F and by the time it weaves back to key of Ab, we begin the trombone solo. Roger (trombone soloist) weaves his way out of three distinct harmonic sections. The A Prime Section section in key of Ab, the C13sus over the C pedal section (Or B section), and then back to the A section in the key of F. The flugelhorn solo has a similar harmonic structure as well. I really wanted to have each solo not start at the “top” of the form, but rather somewhere in the middle. This lets the solos feel like they are floating in the texture of the tune, rather than playing a traditional chorus type improvisation that you’ve heard thousands of times before (Not that there’s anything wrong that…).

3. Sus chords over a pedal point

The intro is the most obvious use of this concept. I use a collective improvisational texture with the piano and guitar (Matt Endahl and Lindsey Miller), to fill the space towards the beginning. When the horns join in, they play fragments of the coming melody (Almost like a mini-overture). All of this is over a C pedal implying a C13sus tonality. I use this sus section two more times in the charts. Again as a transition in the trombone solo and once more at the climatic ending. I develop the ending section more by alternating between a C13sus and C7(#9b13) tonality, but all of it is still over a C pedal. Of note, I always enjoy finding the half steps in certain voicings. In this particular instance, I employed a lot of dissonance between the b7 and 13 of the voicing. This effect is used often behind Roger’s solo and in the introduction.

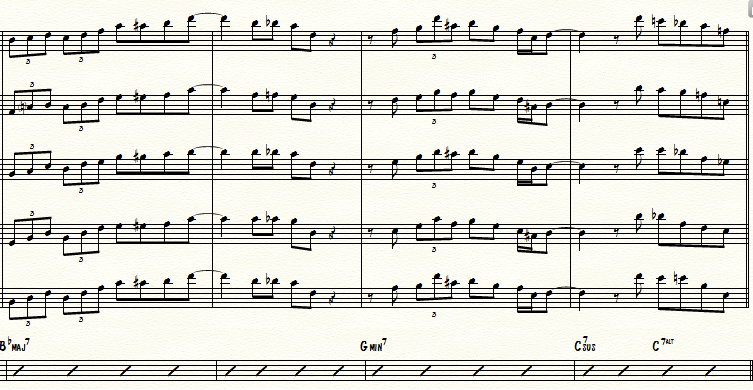

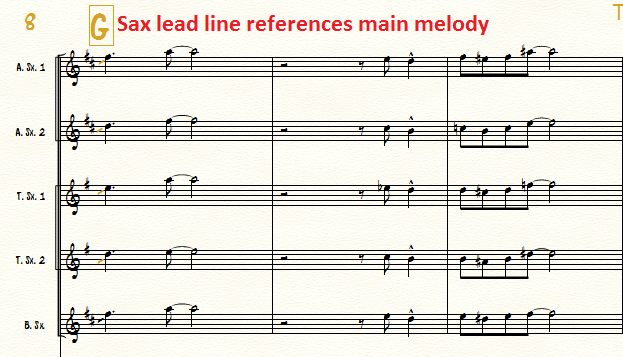

4. Sax Soli

When it comes to this sax soli, I stuck mostly with the classic block style voicings, while going into 5 parts occasionally. My usual approach it do what seems best for the situation. In most Basie style writing, doubling the Alto 1 down the octave in the Baritone is a nice strong cohesive sound. It also sounds very much of the era, which is another way I captured the Basie sound. Here is score view of the first 8 bars:

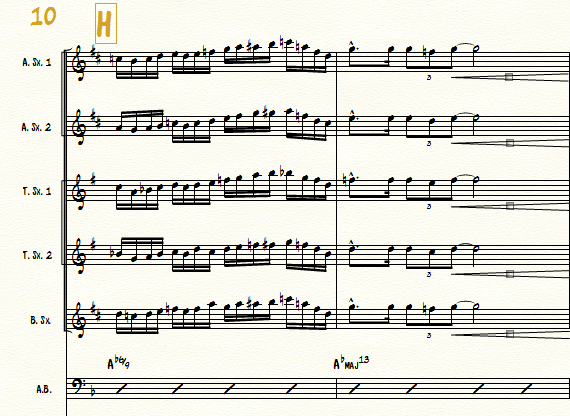

With all solis I aim for singable lead lines, good voice leading (especially in the inner parts), and nice rhythmic variety. I also tried to reference fragments of the melody (m.57-59) and have a climax point (m.73-74).

Measures 57-59, the sax soli references the melody. m.59 includes a small variation on the melody.

Measure 73 is the climax of the soli with the first use of 16th notes, and measure 74 concludes the phrase with a strong ending and crescendo.

5. Feature Jim Williamson (Flugel) and Roger Bissell (Trombone)

The joy of writing for a specific band is I can cater tunes around certain voices. I really thought Jim and Roger would sound nice on this tune and I was right! This also is a consideration for when I write music to be performed live (soloist/style variety) and especially important when I program a CD track flow. One thing I consider when writing big band charts is how I want to approach the improvisational sections. On some charts I opt for a more open and freer approach (The Arch and #Officefortheday are good examples of this – I’ll talk about those two in a later blog post). However for this chart, I decided to have the solos be a determined length and to move with the arch of the composition. For contrast, I start Jim’s solo with ensemble stop-time figures, in order to present it in a more interesting light. While writing, I realized that Jim’s solo was a tad shorter that I would have liked. I looked at making his solo section longer, but it never seemed to jive with the energy at that point in the composition. To give Jim more space, I opted to let him blow a little bit in the intro as a way to introduce himself before going into a full on solo later in the tune.

6. Traditional shout chorus to feature ensemble in tutti.

To be honest, this is something my writing has gotten away from lately, as it can be tiresome to constantly be playing in tutti while performing with big bands. With that said, there is nothing better than a powerful, swinging ensemble in tutti. To earn this climax, I try to keep the orchestration light and tempered throughout the piece. See the intro and the backgrounds behind the solo sections as good examples of this “less is more” approach. But one of the great things about having such a wonderful lead trumpeter, is the chance to show him off. You get to hear the power and accuracy of Steve Patrick leading the wind section for the entire shout chorus. When approaching shouts, I aim for the same qualities as my sax solis: singable melodies, good voice leading and proper pacing. In order to make good phrases, I make sure to have logical starts and endings. This also allows the drummer (Joshua Hunt) to get to fill between figures. Sonny Payne, a drummer famously associated with the Count Basie Orchestra was known for his legendary shout chorus fills and Joshua pays his best homage to this tradition. It’s important to leave space for the drummer to have his/her say! For examples of great shout choruses check out Corner Pocket, Shiny Stockings, and Splanky.

Other wonky points:

-I always have an octave double under the lead trumpet in voiced out sections. This is one of the reasons I love writing for five trumpets. I also enjoy using the guitar 8vb from the lead as well during shout choruses. I’ve noticed this a lot with John Clayton’s writing. It helps solidify the line a bit and it gives the player something to do. With all the harmonic information going on, I don’t really need comping for these bigger moments so I opt to cue the lead line with chord symbols for the pianist when I want more impact. Otherwise, they can choose what or when to play during the big tutti sections. (On a side note: next time you watch a big band perform, pay attention to what the pianist does during shout choruses. Majority of the time they usually sit back and let the horns take it.)

-The last chord is a F7(#9b13). I have the 5th in the top of the voicing with a b13 below (Tenor 1). I remember a rather lengthy Facebook discussion over the difference between a #5 and b13 extension. I’ve always understood b13 to imply that there is a natural 5 in the voicing. This is the sound I wanted in the final chord.

Well I hope you enjoyed this blog post! I plan to do one a week and cover around 4 of the tracks for the album. As always, if you enjoyed this please contact me on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter. If you’d like to pick up the new album you can get it on CDBaby, iTunes, or Google Play.

All the best,

Tyler